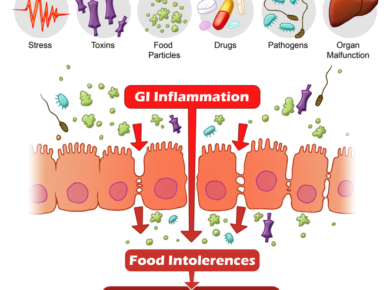

We all know that everything starts in the gut or that the gut is the second brain.

This is very true when it comes to autism, ASD and any other neurological issues.

Every kid who has autism struggles with gastrointestinal issues. You can talk to the parents and they will all tell you that they struggle with their bowels.

Many studies have found differences between the composition of the gut microbiomes in people with and without autism.

But those studies can’t determine whether a microbial imbalance is responsible for autism symptoms or is a result of having the condition.

A group of researchers designed a study to find an answer to this conundrum.

Let’s look at the study “Human Gut Microbiota from Autism Spectrum Disorder Promote Behavioral Symptoms in Mice” published by Sarkis Mazmanian

To test the effect of the gut microbiome on behavior, the scientists put fecal samples from children with and without autism into the stomachs of germ-free mice, which had no microbiomes of their own.

Yes, you read it well. They took samples of poop from children with and without autism and injected them into germ-free mice.

That was a neat experiment and could answer whether or not the gut microbiome has anything to do with the development of autism.

The researchers then ran these offspring through behavioral tests typically used to gauge autism-like symptoms in mice.

Mice with the autism-derived microbiome had lower levels of

several bacterial species that are beneficial. In other words, the

population of good bacteria was much less than in mice without autism-like

symptoms.

Thus, there was a major difference in the gut microbiome between the mice with

and without autism.

The cool thing they authors decided to do is to look at the gut content of those 2 mice populations.

It’s known that microbes in the gut break down or modify the amino acids in food, and that byproducts can travel through the bloodstream and possibly into the brain.

When the researchers looked at the contents of the mouse guts, they found differences between the two groups in the levels of 27 metabolites.

In particular, mice harboring microbes from people with autism had lower levels of taurine and 5-aminovaleric acid (5AV), molecules that are known to bind to neurons and inhibit their activity.

5-aminovaleric acid (5AV) is in the same family of GABA.

Gamma-aminobutyric acid, or GABA, is a neurotransmitter that sends chemical messages through the brain and the nervous system, and is involved in regulating communication between brain cells. Lower-than-normal levels of GABA in the brain have been linked to schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, sleep disorders, mood disorders and pain.

In addition, 5AV is a known molecule that inhibits or prevents apoptosis/program cell death. A high amount of 5AV in the brain prevents the death of brain cells.

These findings fit with the theory that an imbalance between neuronal signals in the brain might underlie autism.

The team also found with a different strain of mouse known to develop autism-like symptoms that feeding the animals either taurine or 5AV led to more social interaction and less repetitive behavior.

In other words, taurine or 5AV improves autism-like symptoms and behaviors in mice!

This study and many others suggest that the microbiome play a role in regulating how people think and feel.

Yes, there is lots of interest in studying how gut microbiome affects the way we think, behave, how our brains function.

Indeed, a growing group of researchers around the world are investigating how the microbiome, as this bacterial ecosystem is known, regulates how people think and feel.

Scientists have found evidence that about a thousand different species of bacteria, could play a crucial role in autism, anxiety, depression, and other disorders.

Some of the most intriguing work has been done on autism and how changes in the gut microbiome can lead to the development of neuronal issues.

Dr. Sarkis Mazmanian has focused on a common species called Bacteroides fragilis, which is seen in smaller quantities in some children with autism.

You can read her paper entitled:

Microbiota Modulate Behavioral and Physiological Abnormalities Associated with Neurodevelopmental Disorders publishedin Cell by Dr Mazmanian.

In this paper, mice with autism were fed B. fragilis. The treatment altered the makeup of the animals’ microbiome, and more importantly, improved their behavior.

They became less anxious, communicated more with other mice, and showed less repetitive behavior.

This is another piece of evidence that the gut microbiome is an important player in autism.

Mazmanian and his colleagues have identified one chemical called 4-ethylphenylsulphate, or 4EPS (member of the benzene family), which seems to be produced by gut bacteria.

They’ve found that mice with symptoms of autism have blood levels of 4EPS more than 40 times higher than other mice!

The link between 4EPS levels and the brain isn’t clear, but when the animals were injected with the compound, they developed autism-like symptoms.

To reinforce this connection, Dr. Stephen Collins from McMaster University gathered evidence that probiotics can reduce anxiety and depression.

He found that strains of two bacteria, lactobacillus and bifidobacterium, reduce anxiety-like behavior in mice.

Humans also carry strains of these bacteria in their guts. In one study, he and his colleague collected gut bacteria from a strain of mice prone to anxious behavior, and then transplanted these microbes into another strain inclined to be calm. The result: The tranquil animals appeared to become anxious.

Overall, both of these microbes seem to be major players in the gut-brain axis.

Another scientist, Dr. John Cryan, a neuroscientist at the University College of Cork in Ireland, has examined the effects of both of them on depression in animals.

In a 2010 paper published in Neuroscience, he gave mice either Bifidobacterium.

He then subjected them to a series of stressful situations, including a test which measured how long they continued to swim in a tank of water with no way out. This test is common in science in order to assess mouse behavior under certain conditions.

The probiotics were effective at increasing the animals’ perseverance and reducing levels of hormones linked to stress.

Another experiment, this time using lactobacillus, had similar results.

So far, most microbiome-based brain research has been in mice.

But there have already been a few studies involving humans.

Last year, for example, Dr. Collins transferred gut bacteria from anxious humans into “germ-free” mice, animals that had been raised (very carefully) so their guts contained no bacteria at all.

After the transplant, these animals also behaved more anxiously.

A paper published in the May 2015 issue of Psychopharmacology by the Oxford University neurobiologist Phil Burnet looked at whether a prebiotic,a group of carbohydrates that provide sustenance for gut bacteria, affected stress levels among a group of 45 healthy volunteers.

The article is entitled:

“Prebiotic intake reduces the waking cortisol response and alters emotional bias in healthy volunteers”.

Some subjects were fed 5.5 grams of a powdered carbohydrate known as galactooligosaccharide, or GOS, while others were given a placebo.

Previous studies in mice by the same scientists had shown that this carb fostered the growth of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacteria; the mice with more of these microbes also had increased levels of several neurotransmitters that affect anxiety, including one called brain-derived neurotrophic factor.

In this experiment, subjects who ingested GOS showed lower levels of a key stress hormone, cortisol, and in a test involving a series of words flashed quickly on a screen, the GOS group also focused more on positive information and less on negative.

This test is often used to measure levels of anxiety and depression, since in these conditions anxious and depressed patients often focus inordinately on the threatening or negative stimuli.

Burnet and his colleagues note that the results are similar to those seen when subjects take anti-depressants or anti-anxiety medications.

That is right, prebiotics had the same results as anti-depressants!

Perhaps the most well-known human study was done by Mayer, the UCLA researcher. He recruited 25 subjects, all healthy women; for four weeks, 12 of them ate a cup of commercially available yogurt twice a day, while the rest didn’t.

Yogurt is a probiotic, meaning it contains live bacteria, in this case strains of four species, bifidobacterium, streptococcus, lactococcus, and lactobacillus. Before and after the study, subjects were given brain scans to gauge their response to a series of images of facial expressions, happiness, sadness, anger, and so on.

The article is:

“Consumption of Fermented Milk Product With Probiotic Modulates Brain Activity”.

To Mayer’s surprise, the results, which were published in 2013 in the journal Gastroenterology, showed significant differences between the two groups; the yogurt eaters reacted more calmly to the images than the control group. “The contrast was clear,” says Mayer. “This was not what we expected, that eating yogurt twice a day for a few weeks would do something to your brain.”

He thinks the bacteria in the yogurt changed the makeup of the subjects’ gut microbes, and that this led to the production of compounds that modified brain chemistry.

Scientists have found that gut bacteria produce neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine and GABA, all of which play a key role in mood (many antidepressants increase levels of these same compounds).

Certain organisms also affect how people metabolize these compounds, effectively regulating the amount that circulates in the blood and brain.

Gut bacteria may also generate other neuroactive chemicals, including one called butyrate, that have been linked to reduced anxiety and depression.

Dr. Cryan and others have also shown that some microbes can activate the vagus nerve, the main line of communication between the gut and the brain.

In addition, the microbiome is intertwined with the immune system, which itself influences mood and behavior.

As scientists learn more about how the gut-brain microbial network operates, Dr. Cryan thinks it could be hacked to treat psychiatric disorders. That’s right!

“These bacteria could eventually be used the way we now use Prozac or Valium,” he says.

“I think these microbes will have a real effect on how we treat these disorders,” Dr. Cryan says. “This is a whole new way to modulate brain function.”

I am glad that science is finally catching up to this very important concept that we have known for a very long time!

Our resident microbes vary based on our environment and diet.

The diversity of microbes in our gut depends on what we put in our bodies. It depends on the food we ingest and the toxins that get into us via air, water, food, and vaccines.

We know that autism (or ASD) is caused by gut dysfunction and microbiome imbalances.

But what causes those microbiome imbalances?

Bad quality food, junk food, GMO, grains, sugar, dairy products are a few factors.

Candida is also an important part of gut issues along with parasitic infestations.

In addition, I see a very important connection between autism and autism meaning that a great majority of autistic kids have Roundup poisoning. Glyphosate is a known gut disrupter. Roundup is present in our food supply and vaccines.

The measles component of the MMR vaccine is also a major player. Several teams of researchers across the world have shown a direct causative effect of this vaccine into the disruption of the gut leading to inflammatory bowels.

As we can see, there are several factors causing ASD and they seem to play a synergistic role into the full progression of the disease.

God bless y’all 😊

Dr. Serge

#thenutritionscientist