Respiratory viruses like coronaviruses and influenza infect us through inhaling droplets or by touching contaminated surfaces, then rubbing our nose, mouth, or eyes.

Viruses can spread further in an aerosol if an infected patient is subjected to an aerosol‐generating procedure such as a nebulizer or mechanical ventilation.

There are two significant classes of facemask:

- medical/surgical masks are loose‐fitting, disposable masks that filter out droplets,

- while tight‐fitting N95 or P2 respirator masks are designed to be more effective filters of airborne particles. N95/P2 masks are more expensive. Both surgical and N95 masks may become a scarce resource.

Evidence on the efficacy of masks is confounded by whether or not they are being used in a pandemic, whether by healthcare workers or the public, and by the concomitant use of hand‐washing, social distancing, and other personal protective equipment.

A meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials of pre‐COVID‐19 showed that surgical masks or N95 respirators reduced clinical respiratory illness in healthcare workers by 41% and influenza‐like illness by 66%: they work but are far from perfect.

N95 masks were not statistically better than surgical masks in preventing proven influenza or preventing COVID‐19, although the latter is based on weak data.

N95 masks are more efficient filters of small particles. Still, these findings suggest it is reasonable to recommend that healthcare workers use surgical masks when there is a risk of droplet spread and reserve precious N95 masks for healthcare workers performing aerosol‐generating procedures.

Some healthcare and ancillary hospital staff have mooted wearing surgical facemasks all the time, even when asymptomatic, to protect themselves and patients.

However, given the current low and declining transmission within the healthcare community, the risk of a health worker inadvertently catching or spreading the infection if not wearing a mask is very low.

Symptomatic healthcare workers should not return to work until they have been tested and found to be negative for COVID‐19.

The public might wear masks to avoid infection or to protect others. During the 2009 pandemic of H1N1 influenza (swine flu), encouraging the public to wash their hands reduced the incidence of infection significantly, whereas wearing facemasks did not.

There is no good evidence that facemasks protect the public against infection with respiratory viruses, including COVID‐19.

During the pandemics caused by swine flu and by the coronaviruses, which caused SARS and MERS, many people in Asia and elsewhere walked around wearing surgical or homemade cotton masks to protect themselves.

One danger of doing this is the illusion of protection. Surgical facemasks are designed to be discarded after a single use.

As they become moist, they become porous and no longer protect.

Indeed, experiments have shown that surgical and cotton masks do not trap the SARS‐CoV‐2 (COVID‐19) virus, which can be detected on the outer surface of the masks for up to 7 days.

Thus, a pre‐symptomatic or mildly infected person wearing a facemask for hours without changing it and without washing hands every time they touched the mask could paradoxically increase the risk of infecting others.

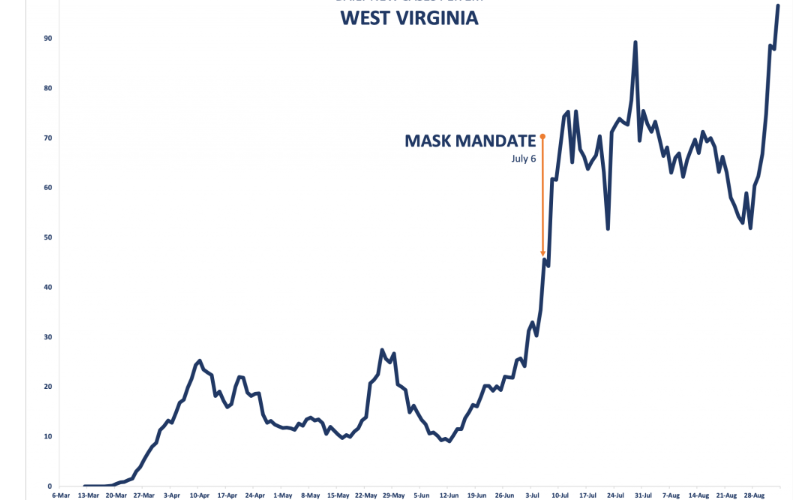

Because the USA is in a desperate situation, its Centers for Disease Control has recommended the public wear homemade cloth masks.

This was essentially done in an effort to try and reduce community transmission, especially from people who may not perceive themselves to be symptomatic, rather than to protect the wearer, although the evidence for this is scant.

In contrast, the World Health Organization currently recommends against the public routinely wearing facemasks.

In Australia and New Zealand currently, the questionable benefits arguably do not justify healthcare staff wearing surgical masks when treating low‐risk patients and may impede the normal caring relationship between patients, parents, and staff.

Science clearly demonstrates that masks are useless for virus protection. Below are some references to support this:

Offeddu V, Yung CF, Low MSF, Tam CC. Effectiveness of masks and respirators against respiratory infections in healthcare workers: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017; 65: 1934–42.

Long Y, Hu T, Liu L et al. Effectiveness of N95 respirators versus surgical masks against influenza: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. J. Evid. Based Med. 2020. 10.1111/jebm.12381.

Bartoszko JJ, Farooqi MAM, Alhazzani W, Loeb M. Medical masks vs. N95 respirators for preventing COVID‐19 in health care workers: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized trials. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 2020. 10.1111/irv.12745.

Klompas M, Morris CA, Sinclair J, Pearson M, Shenoy ES. Universal masking in hospitals in the Covid era. N. Engl. J. Med , 2020. 10.1056/NEJMp2006372.

Saunders‐Hastings P, Crispo JAG, Sikora L, Krewski D. Effectiveness of personal protective measures in reducing pandemic influenza transmission: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Epidemics 2017; 20: 1–20.

Feng S, Shen C, Xia N, Song W, Fan M, Cowling BJ. Rational use of face masks in the COVID‐19 pandemic. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30134-X.

Chin A, Chu JT, Perera M et al. Stability of SARS‐CoV‐2 in different environmental conditions. Lancet Microbe , 2020. 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30003-3.

In addition, I blogged intensively about this:

Furthermore, masks reduce oxygen in our body:

Masks increase the risk of infections:

And finally, masks cause violent behaviors in facemask users:

God bless y’all 😊

Dr. Serge