We have heard a lot about intermittent fasting over the last few years.

Actually, earlier, it was Google’s hottest trending dietary search in 2019, it was the most practiced weight-loss intervention among female physicians, and a new pilot study showed 14:10 time-restricted eating promoted weight loss and metabolic health.

You can read more about this pilot study:

“Ten-Hour Time-Restricted Eating Reduces Weight, Blood Pressure, and Atherogenic Lipids in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome” published at

https://www.cell.com/cell-metabolism/fulltext/S1550-4131(19)30611-4

Now the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), arguably the most prestigious medical journal, published a review article promoting the benefits of intermittent fasting and time-restricted eating:

“Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Health, Aging, and Disease.”

This is the link to the study:

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra1905136?query=featured_home

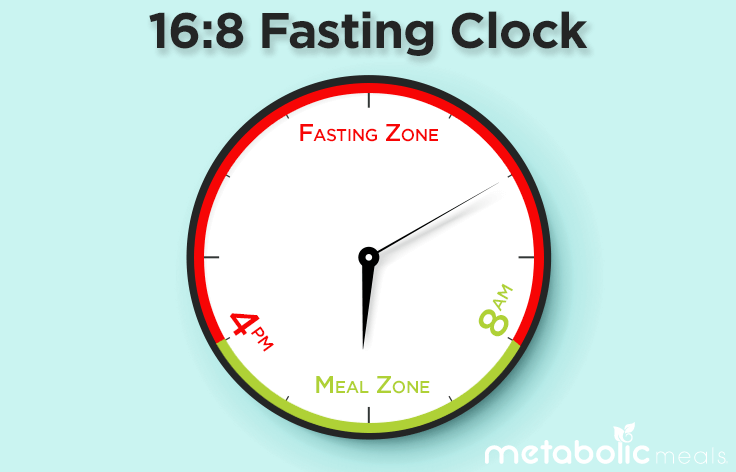

Intermittent Fasting is basically just a very general term to describe an eating protocol that relies on modifying the timing of when you consume your food. What it implies is basically that instead of eating your meals spaced throughout the day as is generally recommended, you save all of your caloric intake for a specific limited period of time and don’t consume any food at all in the meantime.

But does the evidence support the hype? The new review article seems to think so.

The review article makes a strong case that, yes, intermittent fasting does promote health beyond simple weight loss. Specifically, the authors refer to the metabolic shift that occurs when we stop burning glucose for fuel and instead burn fatty acids. As a result, we produce ketone bodies which have multiple potential cellular benefits, and we can tap into autophagy, a cellular remodeling, and regenerative process”

“During fasting, cells activate pathways that enhance intrinsic defenses against oxidative and metabolic stress and those that remove or repair damaged molecules.”

“Ketone bodies are not just fuel used during periods of fasting; they are potent signaling molecules with major effects on cell and organ functions. Ketone bodies regulate the expression and activity of many proteins and molecules that are known to influence health and aging.”

They also point to evolutionary mechanisms that promote cellular health:

“Repeated exposure to fasting periods results in lasting adaptive responses that confer resistance to subsequent challenges. Cells respond to intermittent fasting by engaging in a coordinated adaptive stress response that leads to increased expression of antioxidant defenses, DNA repair, protein quality control, mitochondrial biogenesis and autophagy, and down-regulation of inflammation. “

While we have to admit most of the evidence for this comes from non-human studies, human studies are catching up. The NEJM review does a nice job of referencing the growing body of literature in humans showing greater insulin sensitivity and abdominal fat loss with intermittent fasting than would be expected from weight loss alone.

This highlights one of the challenges in discussing the science of intermittent fasting. Are we talking about a 14:10 eating window? Is that different than a 16:8, or a 23:1 (just one meal a day, also called OMAD)? What about alternate day fasting, or a 5:2 schedule?

Despite the growth of the literature and the vast anecdotal success, we have to admit there is still much we do not know from a scientific perspective. But I think we can all agree with their conclusion:

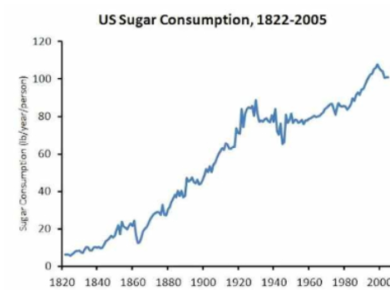

“A diet of three meals with snacks every day is so ingrained in our culture that a change in this eating pattern will rarely be contemplated by patients or doctors. The abundance of food and extensive marketing in developed nations are also major hurdles to be overcome.”

Fortunately, increased media attention, promoting success stories, and peer-reviewed journal articles show promise in improving these hurdles. The fact that 75% of surveyed female physicians use intermittent fasting for their own weight loss is encouraging for the future of mainstream medical use.

Their next conclusion is also one we can easily address:

“On switching to an intermittent-fasting regimen, many people will experience hunger, irritability, and a reduced ability to concentrate during periods of food restriction.”

This is where the combination of low-carb nutrition and intermittent fasting has great promise. While head-to-head studies don’t exist, most low-carb clinicians agree that eating an LCHF diet makes intermittent fasting much easier to achieve thanks to greater satiety and suppression of hunger hormones.

Indeed, eating a high-fat diet stabilizes your blood sugar and minimizing hunger and cravings during the fast.

Fasting has the potential to delay aging and help prevent and treat diseases while minimizing the side effects caused by chronic dietary interventions

But how?

Fasting WORKS because it stimulates autophagy.

But what is it? The word derives from the Greek auto (self) and phagein (to eat). So, the word literally means to eat oneself. Essentially, this is the body’s mechanism of getting rid of all the broken down, old cell machinery (organelles, proteins, and cell membranes) when there’s no longer enough energy to sustain it. It is a regulated, orderly process to degrade and recycle cellular components.

Fasting is actually far more beneficial than just stimulating autophagy. It does two good things.

By stimulating autophagy, we are clearing out all our old, junky proteins, and cellular parts.

At the same time, fasting also stimulates growth hormone, which tells our body to start producing some new snazzy parts for the body. We are really giving our bodies the complete renovation.

So, here’s the deal. There is some good scientific evidence suggesting that circadian rhythm fasting when combined with a healthy diet and lifestyle, can be a particularly effective approach to weight loss. All that time spent not eating any food will stimulate your body to release fat from storage, and since you won’t have any nutrients from food in your bloodstream to use for energy, your body will use the energy from its own fat stores! The circadian rhythm fasting approach is, where meals are restricted to an 8-hour period of the daytime.

5 ways to use this information for better health:

1. Avoid sugars and refined grains. Instead, eat fruits, vegetables, beans, lentils, proteins, and healthy fats (olive oil, avocados, coconut oils, eggs, grass-fed butter, ghee, etc.).

2. Let your body burn fat between meals. Don’t snack. Be active throughout your day. Build muscle tone.

3. Consider a simple form of intermittent fasting. Limit the hours of the day when you eat, and for best effect, make it earlier in the day (between 7 am to 3 pm, or even 10 am to 6 pm). The goal is to eat over a period of 8 hours, whenever it is convenient for you.

4. Avoid snacking or eating at nighttime, all the time.

5. Get a good night of sleep

Let me know your experience with intermittent fasting 🙂

Dr. Serge

@DrSergeTheNutritionScientist